Historically, financial services companies have focused their efforts on attracting and satisfying customers who have plenty of money. This is an obvious play for businesses which rely on their customers’ stored capital to make a profit. With income disparity on the rise and an increasingly global market for financial products, especially mobile-enabled and online ones, smart banking and insurance companies are starting to reconsider the limitations of targeting affluent customers as their main audience. While low-income customers may seem like a risky or undesirable market in the terms of standard underwriting, or may seem to costly to create and manage accounts for, microlending and social-lending pioneers have found that the default rate on loans to traditionally unfinanceable individuals is much lower than the average for conventional borrowers. When merged with the social and economic benefits of improving quality of life and financial literacy for broader range of people, these early experiments in alternative financing represent a compelling area of opportunity for companies who are interested in expanding their market and innovating across a broader spectrum–perhaps drastically lowering new customer onboarding and maintenance costs for previously unprofitable demographics.

Open APIs

Open application program interfaces, or APIs, are a way for financial services companies to access and fetch or send calls to other organizations’ systems. For example, Authorize.net’s API allows merchants to send a call for a transaction authorization and receive a verification back. Few financial services APIs exist, and even fewer allow interoperability without extensive relationship-building with the host of the data. Interoperability issues related to legacy systems, regulatory concerns and hesitancy to disclose too much data to competitors or disruptors are among the factors that hold companies back from exploring the opportunities that APIs could provide for financial services providers. In other words, unlike the social media industry, mobile industry or other places where innovation is enabled by the availability of robust, well-designed APIs, most of the financial industry has not yet made it possible for third parties to create value on top of their platforms.

Key developments in the open financial API space include:

- Fidor Bank—a German online-first bank with a robust API

- Ripple—a cryptocurrency-based financial infrastructure allowing all manner of payment and transfer-related transactions through an API and their own ‘metacurrency,’ permitting both end users and developers to create robust financial services products without having to create their own infrastructure

- Digital Financial Services for the Poor—a platform for global poverty alleviation in development by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation , which is creating a semi-open API for digital money and digital transactions such as deposit accounts, cash-equivalent payments, basic insurance products and currency exchange with the goal of enfranchising the unbanked and underbanked.

Crowdshared Risk and Reward

Unmet needs in lending and insurance have given rise to many alternative models which rely on shared risk and/or shared reward as a way of supplementing—or even replacing—traditional models for managing and rewarding risk. One example of this is Friendsurance, a peer-to-peer ‘social insurance’ company based in Germany which invites customers to opt in to a group policy which is shared between friends. Each group policy includes a pool of money, fed by a percentage of each member’s premium, which can be used to pay out small claims. If, at the end of the year, there is money left in the pool, everyone gets their share of the remainder back. Part of the premiums still go to regular insurance, but the idea of money back each year underwritten by the desire to do right by your friends is an attractive value add—especially for people who see collaboration, community and “pay only for what you use” as part of their cultural identity. Lending has some examples as well, most notably Lending Club (backed largely by Wells Fargo) and their new competition Karrot. Both lending innovators offer personal loans of up to $35,000 in a campaign-style model that resembles Kickstarter, except with investors getting a return on their money and borrowers paying back what they receive at a lower interest rate than they would for most bank loans or credit cards. These types of market, distribution, product, and community innovations around risk and profit sharing also create a perfect environment for digital platforms to emerge, with an active community of players and value-creators but not too much customized plumbing needed on the backend.

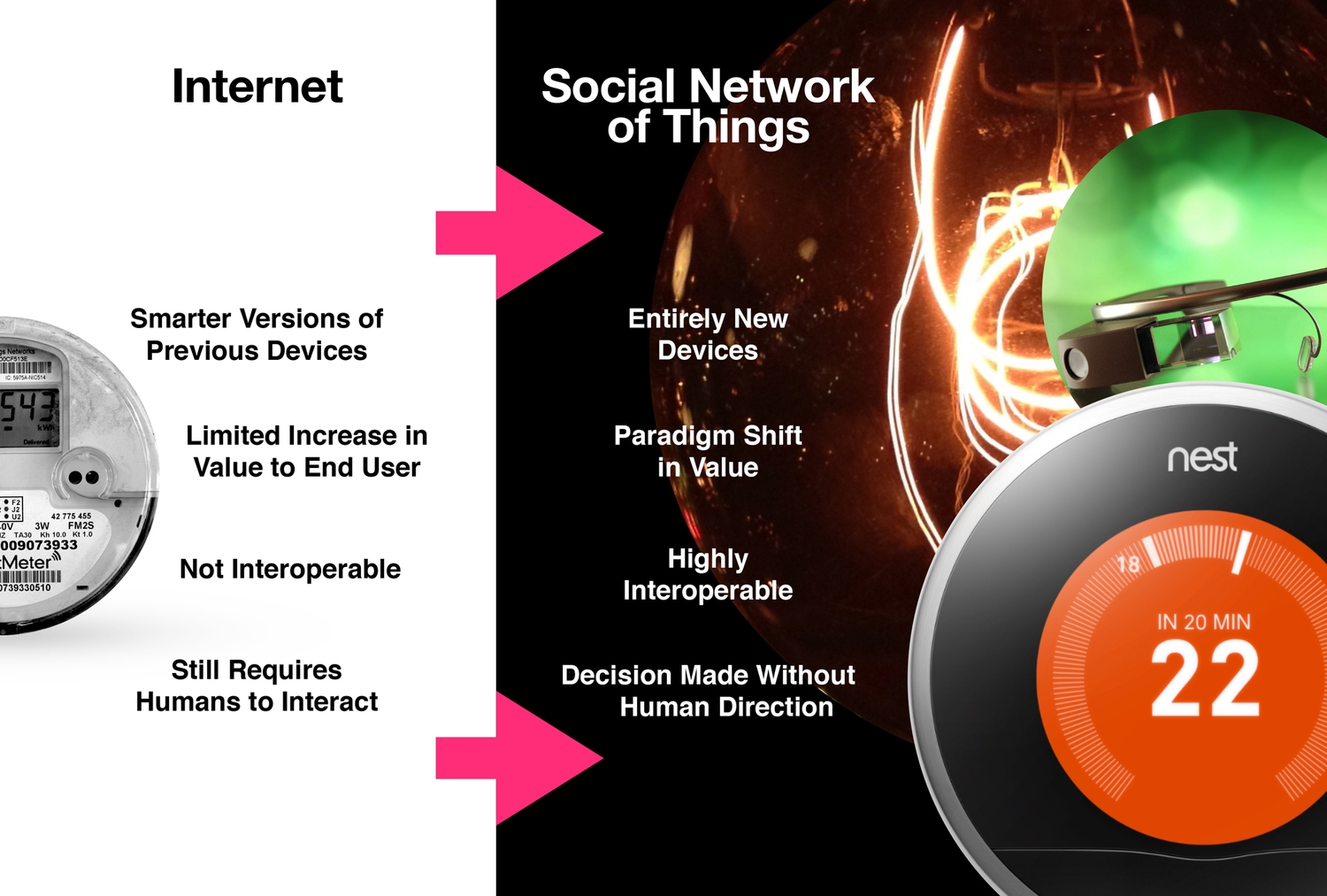

The Social Network of Things

At the apex of the Information Age—and just a few years out from the Internet of Things—is a time when devices and people are connected through pervasive internet access, a rich web of sensors, advances in artificial intelligence, deep APIs and cultural changes. This near future is the Social Network of Things, the complex ecosystem of exchange and collaboration between machines themselves and the beginning of a change in the fundamental ways human beings relate to their bodies as they are augmented with technology.

As machines become increasingly autonomous and connected, they, too, need financial services. Machine-to-machine (M2M) communications often signal M2M transactions. As such transactions—maybe a request for server time, or a more tangible outcome like vacuuming an apartment floor—become easier and easier to separate and track in detail, we might find that they are coupled with a need to exchange value. What if you didn’t keep all of your own cleaning devices, but your apartment building had devices which went from apartment to apartment on their own. If you had a particularly dirty or particularly clean wood floor, the building’s refuse system and water supply system might charge the floor cleaning device accordingly and apportion that charge to your account. Or your electric car might have to manage payments to—and from—its various interactions with power grids, chargers, data bandwidth and traffic or routing information servers.

A more commercial example could come from John Deere—the tractor company. Their increasingly automated farm equipment is part of a larger ecosystem of smart crop management. So what might be possible if there were an easy, extensible payment system for a John Deere tractor to purchase consumable supplies or energy from another brand’s devices? How might we manage identity and avoid fraud if no human is directly involved in the transaction, or if the transactions are micro transactions compared to what we are used to as humans? If such a system was not reliable, food production could be affected. Conversely, a successful autonomous supply and payment network could mean that farmers would only have to pay for what they actually use in terms of supplies, potentially lowering costs or increasing yields—especially if such technologies were properly integrated with big data analytics and other tools.

Millenials and Asset-Light Lifestyles

Millennials are a hot topic in almost all discussions about identifying new markets and products. When looking the future of financial services and especially digital financial services, understanding the way that millennials use and purchase financial products is key, and much of the research about this demographic leads us to reconsider common assumptions about what these customers want and need. For example, while millennials tend to be more worried about the future as a result of the political, environmental and economic crises of their time, one outcome of that skepticism is that they also seem to be more concerned about the future and more interested in self-directed saving and investment than the generations before them.

At the same time, there are some major characteristics in the millennial lifestyle that impact their financial service needs. According to Kleiner, Perkins, Caufield and Byers’ Mary Meeker, many young professionals and creatives are asset-light, choosing to rent rather than own their homes, using on-demand services for transportation rather than personal vehicles, and spending money on things like travel and wellness which offer an experiential value that is transitory. While their portfolio of insurable or appreciable assets tends to be slim, they are very interested in liquidity and are willing to make investments based on their values and interests. Products which aim to serve millennials will also need to account for the ways in which these empowered customers decide what products are right for them—interactivity, customization, and interoperable features are more likely to attract them than a

company’s tenure.

Big Data

Big data is having an enormous impact on the financial services industry, especially in fraud prevention. Analysis of customer spending patterns has allowed companies to identify “red flag” transactions and patterns of activity which are likely linked to a stolen card or identity. This is great news for companies who have been losing millions each year to credit card fraud, but it’s also great for customers whose information is stolen. Frost Bank’s two-way text alert option will send users a text when there is a suspicious transaction posting to their account. The speed at which transaction data is processed now allows the bank to alert a customer in real-time and the two-way option means they can authorize or decline the suspicious activity with a text reply. The customer is saved the embarrassment of standing on the phone in front of a merchant with a line of customers or a declined card at their next point-of-sale, while the bank is saved the administrative costs associated with processing travel notifications and making direct calls to the customer for authorization of flagged transactions.

Little data also becomes its own product. Insurance companies’ fates are decided by how well they balance price and service with the statistical models they use to underwrite customer’s risk profiles. If Metromile or companies like them—due to user-granted access to rich, detailed data—can better predict risk, they can offer services at a lower price and/or higher profit margin. But they can also sell access to that actuarial model to other companies, allowing them to focus on what they do best so far: creation of a compelling brand which has users’ interest and rapid accumulation of data. Jesse Beyroutey, a venture capitalist specializing in the field, calls this exchange ‘data diplomacy’—a new business model defined by data-sharing partnerships between companies. In the coming decade we’ll continue to see innovative companies which want to offer customized and easily updated products—but also to inform their own statistical models for the best pricing and profit margins—creating little data agreements with their customers as a way of informing credit offers, insurance premiums, interest rates, and financial management apps.

“If you want to build loyalty, spend less time using data to tell customers about you, and spend more time telling them something about themselves.”

Little Data

While big data is fueling innovations which largely benefit big companies with access to huge pools of information, companies and individuals are also finding value opportunities informed by little data—detailed information about an individual person. Little data includes just about every type of data a person produces: schedule, shopping choices, patterns of travel, temperature preference in home or car, physical health, emotions—if you can measure it through a sensor or interface, data about humans can be collected and analyzed. The key issue is that you have to get permission from someone to collect their data, but with opportunities for innovation at nearly every point of the spectrum related to little data it is increasingly appropriate to start asking what your users want in exchange for theirs.

Asset management startup Trov has formed an appraisal and insurance platform based entirely on the value of little data. Users upload information about their tangible assets, add new purchases through a mobile app, receive updated information about changes in the value of their possessions, share that information with their insurers for accurate real-time adjustments in coverage, and have the option to sell valuables through Trov’s connection to “specialized marketplaces” online. Having real-time, detailed information about customers’ assets and purchasing behavior is a clear benefit for the insurers who are partnering with Trov, and users are getting more customized service from features and partners in return.

Metromile is a car insurance company which offers customers a deal—they put a sensor in their car which tracks their driving habits and pay an insurance premium which is tailored specifically to their vehicle use. The benefit for both parties is clear: customers pay only for the amount of coverage they actually need, and Metromile gets detailed information which helps them protect themselves from risk. Other car insurance companies have used in-vehicle sensors to offer discounts for safe driving behavior, but Metromile is the first to incorporate little data in an on-demand model of insurance where customers who drive less pay less—by the mile.

Where are the Multi-Sided Platforms for Finance?

Creation of multi-sided platforms requires firms on all sides of a market to examine key technological strategies—like enterprise architecture, machine learning, development operations, legacy system migration and security, among many others. It also requires evolution of innovation cultures, especially in larger firms, where the need for interaction with external partners requires finding ways to open up previously protected and isolated departments.

An opportunity exists for large companies to take on innovation in the financial services industry in a new way, designed to include, rather than resist, small, disruptive players. Certain functions are perhaps best served by large, existing companies—like account management, asset management, and data diplomacy or big data platforms—while new players can partner with existing firms to bring a fresh view on brand, relationship, community and machine learning. This approach, tapping into a broader spectrum of innovation, could be best served by the creation of multi-sided platforms in the financial services industry. Why not create something compatible with other financial players? While many answers come up on both sides of the argument, it’s clear that new technologies, new business models and new customer expectations are here to stay.